The Static of the Line

In the US the first commercial televisions began to take off in the late 30s, with RCA beginning regular broadcasting by 1939. By the 50s television sales exploded, and so began the attraction to the hot electric glow mesmerizing almost every American. In 1965 Sony released the first portable video recording device, the Portapak, and so there was a more cost efficient approach to this new exploration in documentation. Footage could be recorded and played back with instant gratification.

While it was both Andy Warhol and Nam June Paik that were showing video art in the early 60s, Paik was first said to have presented his recorded video as art. In 1965, with a Portapak video recorder, Paik sat in a taxi cab and documented Pope Paul VI traveling through New York City. Only later that day did Paik display his grainy, hardly edited footage in Greenwich Village, thus becoming the pioneer and father of video art. For artists, it was a chance to explore and their yearning to harness a new frontier and embark on an unsullied territory.

The Lines of Resolution: Drawing at the Advent of Television and Video is an adventurous and bold examination of the digital screen, the analog television, and video systems. The fresh exhibition is co-curated by Dr. Anna Lovatt, Associate Professor or Art History at Southern Methodist University, and Kelly Montana, Associate Curator at the Menil Drawing Institute. The idea was to survey a series of works by a rounded collection of predominant artists studying the static of the line. How does one draw with a digital signal? How does a drawing on a piece of paper based in reality penetrate the glass tube of a TV or daily creative annotations perceived through the view finder of the camcorder?

Nam June Paik Zen for TV, 1963 (executed 1981) Altered television set 22 13/16 × 16 15/16 × 14 3/16 in. (57.9 × 43 × 36 cm)The Museum of Modern Art. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, 2008

Spanning four decades, from the 1950s to 1980s, the pieces leave digitized traces of information to build a comprehensive timeline. Prior to the press preview and opening on the 3rd of October, I was eagerly anticipating what might be presented. The Menil Drawing Institute has set its bar high and has been bending and blurring the lines of what drawing can actually translate to, carrying the art form far past the point of a pencil. There was a curiosity building to a crescendo of what the quality of the line through video could be redefined as and how it would be interpreted.

The Lines of Resolution is broken into 5 themes: Scanlines, The Screen in the Studio, Mirroring and Monitoring, Feedback, and Interference, each taking the viewer through multiple rooms and a diverse range of creative investigation. Entering you are greeted with powerful images by the brilliant Nam June Paik. Zen for TV burns a white line into the screen as bright as the stark vertical beam burns into the viewer’s vision. A medium unassuming black VTR monitor turned onto its side. A subtle gesture which works so well.

Nam June Paik

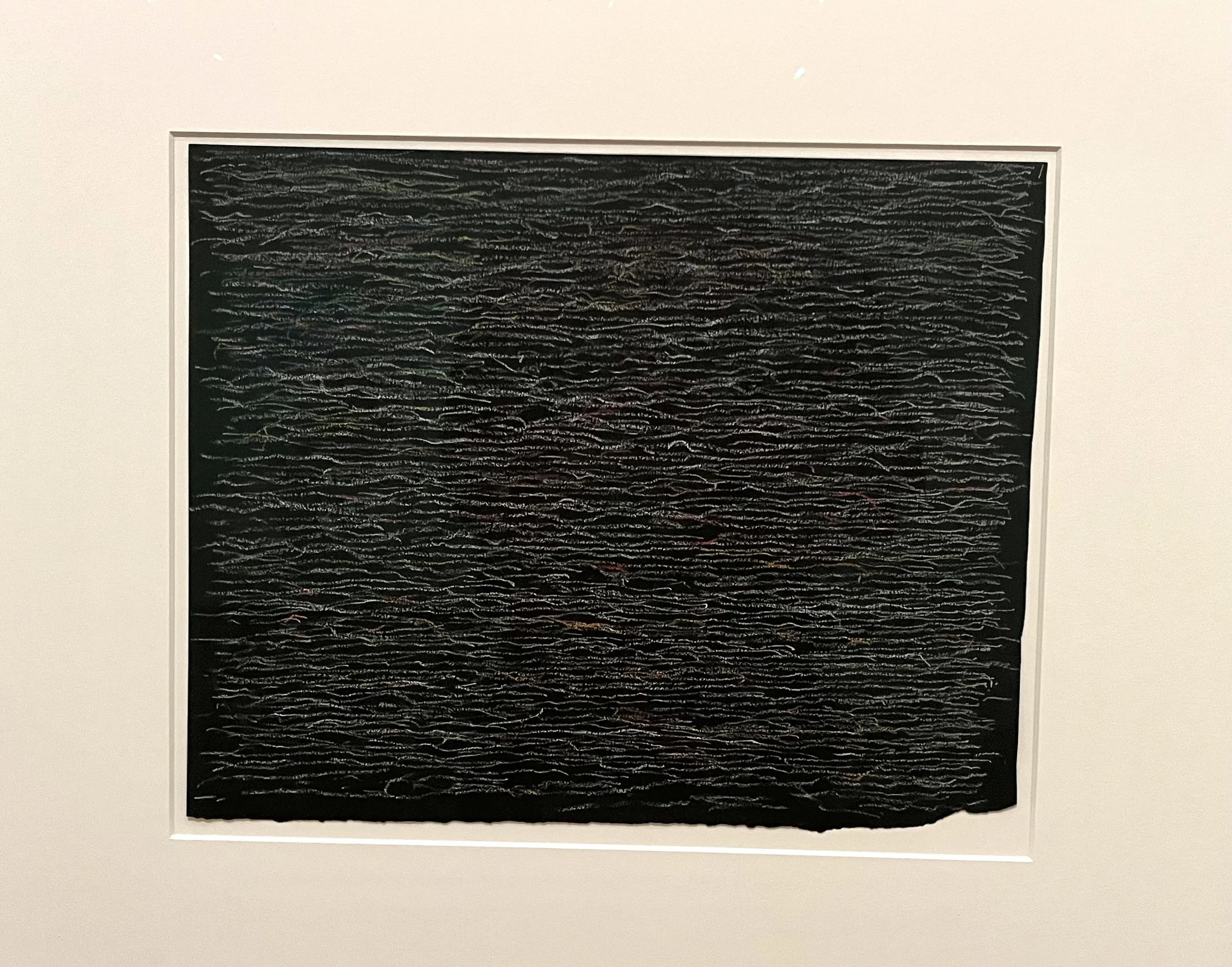

Untitled, 1975

Pastel on black paper

Nam June Paik is the forefather of video, monitor, and digital assembly, and it's not uncommon to see dozens of screens at once in his work. Here, the minimal display is an ember set to ignite the entire exhibition. A single note or love letter portrayed from this one single glowing relic. The artist uses the less-is-more principle, or so it would appear until you move in closer to witness the chaos. Other static intrigues are presented in his micro mark making, mimicking the information in micro bursts on the paper. Repeated over and over again, small images combine as a whole to form what appears to be a rectangle or screen. Another all black, static, rain, or is it snow. As children, I'm sure we all at one time turned the stations until we came across the “snow” of information and broken pictures, sitting front and center with our eyes fixed. Can you hear or see it? The white noise takes over, and our minds meld with the tube creating an imaginary realm of images.

The abstract drawing becomes a moment of reflection or lost explanations, leaving you only with raw sound within the mind. The gestures are transcribed in duplication and blanket the senses with the lost-in-translation noise of mark notations in K.O. Gotz’s Statistical Metric Raster. A collective unconscious nod to both Nam June Paik’s Zen for TV’s vertical beam and his static drawings. All of which reference the construction of the electric signal by the movement of the electron beam, the process of energy translation. The horizontal line traced by the beam is known as the “Scanline,” and the combined lines become a “Raster Pattern”. Gotz’s insane squares and almost invisible system are a bee's hive of information and tonal washes for the eyes. Impressive in scale as they are absurd dedication, but work so harmoniously with the other works in the room.

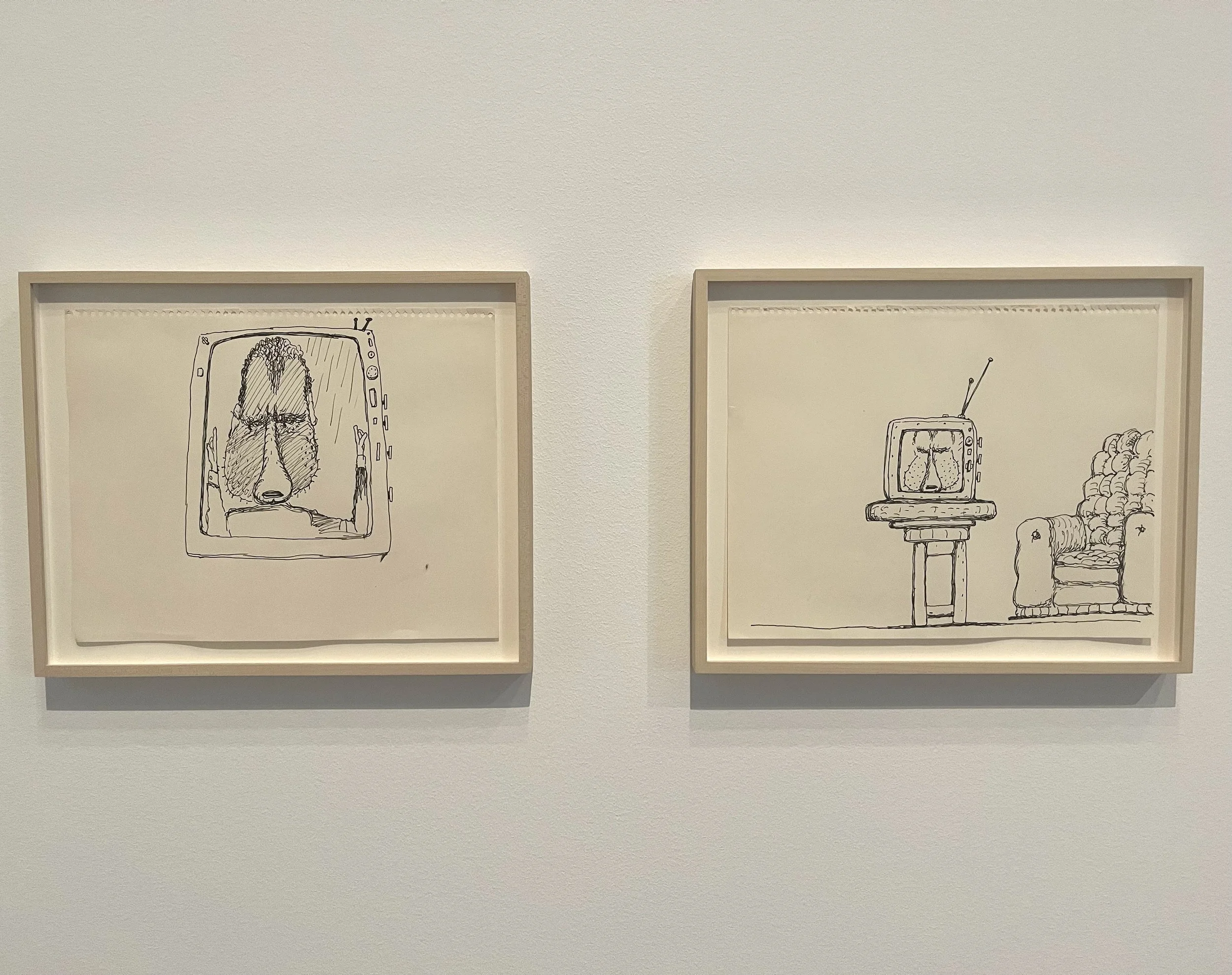

Phillip Guston, untitled 1971, ink on paper / Phillip Guston, untitled 1971, ink on paper

The Screen in the Studio and its gallery is much more literal. Robert Rauschenberg's obsession with soap operas as well as the representation of The TV in modern day culture throughout the 50s and on. Beautiful and almost tranquil drawings by Phillip Guston portraying Tricky Dick on the television screen. Is it Guston’s own images relayed on the screen only then to be recorded back through his very hand? Maybe it's a moment in time of Nixon infiltrating our homes or Guston’s studio, beginning the political and TV invasion of our private spaces? Other works by Richard Serra and his collaboration with Gerry Schum, Walter De Maria, and Dennis Oppenheim flip the script of art making, how its received, translated, and the delivery system with which it's viewed.

The videos in Mirror and Monitoring are lined up to flank the visitor. Individual screens float off the ground, inviting the viewer to engage one at a time or to stand in the center of the room catching the visual cues of gesture making and the documentation of drawing in various forms all at once. Joan Jonas the monumental sculpture / performance artist made her metamorphosis into video performance art shortly after her visit to Japan in 1970, procuring her first video camera. Inspired by the powerful Japanese visual and movements of the culture’s theater and dance, Jonas rendered her own practice down to an alter ego, “The Electronic Erotic Seductress”. Through her androgynous proclaimed persona she dissects, intersects, and inflames the image of self.

Joan Jonas

Left Side Right Side, 1972

Single channel video, black-and-white with sound

Image: Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

In Jonas’s Left Side Right Side, the artist hovers in between a spatial ether. Splitting her image of what is now and what is reflected or assumed. Dancing in the ambiguity of who one is and what we or others translate us to be. Through drawing on herself she recreates or reinvents identity. The black and white grainy video is captivating and hypnotic as it floats behind the vale of a perceived dream state. Mirroring the concept, Anne Bean and Dov Eylath’s color video Blue for You, 1981 depicts Bean covering her face with an unseen medium. With each mark, her skin and self vanish, slowly revealing Eylath behind. The two whisper confessions of who we are as individuals and with another person, more and more of one disappears with the other becoming dominant. Eylath seems reluctant to become part of Bean as she is still removing herself and revealing more of him. As we draw our ideas upon each other with friends or lovers, do we leave enough behind to be recognized? By the end there is only an Anne Bean voided shape that remains, a hollow space of who she once was. The work is heavy with poetic sadness, yet the pair resolve with content and tranquility.

Anna Bean and Dov Eylath

Blue For You, 1981

Single channel video with sound

Image courtesy of Menil Collection

A glowing blue monitor beacons you into the realm of Feedback. In Nina Sobell’s EEG: Video Telemetry Environment a couple sits silently leaning upon each other only communicating with micro motions. A smirk or a smile, a light nudge, the bumping of their heads as a floating squiggling line prances playfully in the center of the screen. The erratic quivering line is the collective brainwave patterns produced by the two volunteers and visually transcribed onto the screen using an oscilloscope as well as recorded on paper in a nearby room during its original conception. This was all part of a revolutionary project Nina Sobell executed in 1975 at the Contemporary Art Museum here in Houston, part of the exhibition Gulf Coast, East Coast, West Coast. With over 150,000 dollars of equipment at the time, the first portable oscilloscope, and help from NASA, the then 28 Sobell invited participants to come to the museum in pairs and sit in a mock living room type, cramped setting. The pair would be hooked up to the machine, watching a live recording of themselves with the dancing brain frequency transposed over them. They had a small amount of control over the monitor with their own abilities while hooked up making mild adjustments to visuals like color with their frequencies.

Playing off the four brain wave patterns Delta, Beta Theta, and Alpha, each changed the color seen layered over top of the pair's own image. The idea was to make the straight wiggling line more and more like a circle, thus indicating they were synchronizing their consciousness through a sort of group meditation. Sobell, in attendance at the opening of Lines of Resolution, stated, “It was quite the collection of technology and science. It was all so new, and there were people lined up around the block all day to participate.”

Nina Sobell

EEG: Video Telemetry Environment, 1975

Single channel color video with sound

The video display itself was on a pedestal with a case to the left featuring one of the long readouts of the oscilloscope and the attached mechanical arm that was charting the waves. The young man and woman seemed to be in a quiet, hypnotic bliss, the blue screen and now circular pattern indicated good things. “That's it, they did it, they are synchronized,” Sobell said with excitement and clasping her hands. Of course, this synchronization was 50 years ago, but the purity and beauty of a couple’s mind drawing was enlightening to watch if only for a handful of minutes.

The exhibition concludes with Interference, three artists intercepting and reconfiguring television messages, as co-curator Kelly Montana described. Howardena Pindell’s mark-making and swarming data points are laid over a live TV broadcast, as they created on top of what was actively being transmitted and broadcasted to her own television. A still of a hockey game and a capture of the Starship Enterprise are almost lost under a bird's nest of numbers and mad, wonderful scripplings to reproject a new dialog.

Artists Anna Bella Geiger and Teresa Burga use translations and transcriptions to protest and fight against ongoing government infiltrations from the military, which smothered them and those around them throughout Brazil and Peru. Burga’s installation 4 Mensajes ( 4 Messages ) extracted signals and dialog from Peruvian television broadcasts in 1973. The works were a not-so-silent protest, and the artist would go on to create non-fundable work in her home country of Peru, making the pieces and the power of her mission that much more valuable.

Lines of Resolution is an experience to be had multiple times over. I found myself back the next day to really sit with each piece and engulf myself with each of the artists’ own excavations of self, a new televised environment, and how they could harness the invasive medium to their advantage or even disadvantage. A Nurture Vs Nature driven by electric ecstasy and what we might capture using it. Give yourself the time to absorb this exhibition at the Menil Drawing Institute, just don’t sit too close because, you know, you’ll go blind.